Beyond “Burning Paper Money”: The Meaning of an Ancient Ritual

In today’s interconnected world, we’re constantly learning about customs that may seem unfamiliar at first. One such tradition, known in Chinese culture as “proxy burning” or joss paper burning, is often seen by outsiders simply as “burning paper money for the dead.” But there’s much more to it.

This practice is a rich, evolving part of family and cultural life—a way to express love, honor ancestors, find comfort, and feel connected to those who have passed away. It’s less about superstition and more about memory, respect, and emotional continuity.

In this article, we’ll look beyond simple labels to understand how this ancient ritual helps bridge past and present, the living and the departed, and the individual with their family story.

Part 1: What Is This Ritual Really About?

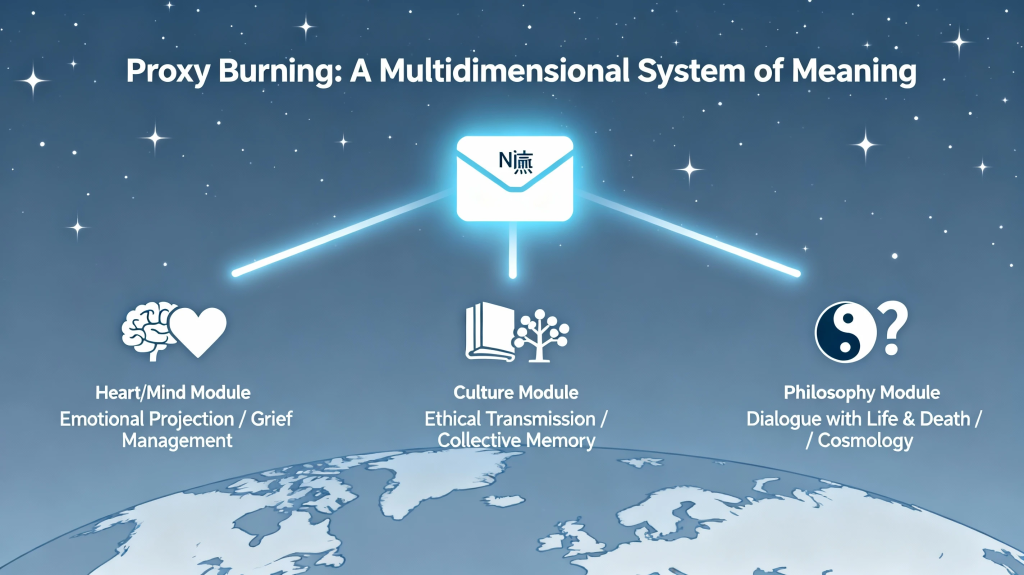

Understanding the Ritual: A Multilayered Practice

The tradition of burning ritual offerings—often called “proxy burning”—can be thought of as a deeply rooted practice that serves multiple purposes at once. It operates on several meaningful levels:

1. Emotional Expression

At its heart, the ritual offers a structured and respectful way to express feelings that can no longer be shared directly with a loved one who has passed away. The act of burning symbolic items gives tangible form to emotions like longing, love, regret, or unspoken words, serving as both a farewell and a way to maintain a sense of connection.

2. Cultural and Family Values

Rooted in traditions of filial piety and ancestor respect, this practice is a visible way to honor family bonds and responsibilities. By passing down the ritual through generations, families strengthen their sense of identity, history, and continuity.

3. Symbolic and Psychological Comfort

This ritual draws on symbolic actions to bring comfort. From a modern psychological view, it can be seen as a form of meaningful activity that helps process emotions. The physical actions—burning to “send,” making offerings to “sustain”—serve as metaphors that help people release grief, reduce anxiety, and reaffirm their intentions toward the departed.

4. Community and Connection

These rituals are often communal, especially during festivals like Qingming or the Hungry Ghost Festival. They bring families and communities together, reinforcing social ties and cultural continuity.

Part 2: A Modern Take on the Ritual – A Structured Practice for the Heart

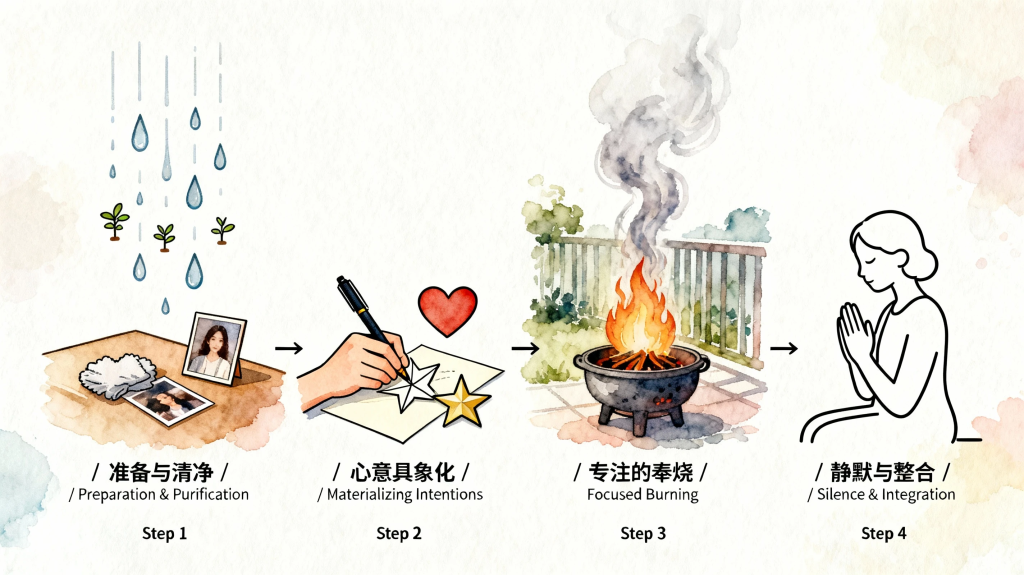

A modern reinterpretation of this practice focuses less on formal rules and more on inner meaning. It can be understood in four key stages, where intention matters more than outward form, and the process itself is as important as the outcome.

Stage 1: Creating a Focused Space

·Traditional aspect: Choosing a suitable time, cleaning the area, setting up an altar.

·Modern meaning: This is about preparing mentally and emotionally. By tidying a space and removing distractions (like phones), you create a physical and mental “ritual space” dedicated to memory and reflection—much like settling in before meditation.

·What to do: Pick a quiet moment. Clean a small area. You might place a photo or a personal item belonging to the departed there.

Stage 2: Giving Feelings a Form

·Traditional aspect: Writing the loved one’s name and preparing symbolic paper offerings.

·Modern meaning: This is the core creative step. What you choose to “send” reflects your thoughts and feelings. Are you writing a letter to share news? Making a paper symbol to express a wish? The object becomes a carrier of your emotion and intent.

·What to do: Write down what you want to say. Or choose/create a simple symbol that has meaning for you—like a flower for love or a small boat for safe passage.

Stage 3: The Act of Letting Go

·Traditional aspect: Lighting the offerings while speaking quietly.

·Modern meaning: Safely lighting the item is a powerful act of symbolic release. Watching the flame is central—it’s a visual metaphor for transformation. This moment becomes a private, personal time for inner conversation, expressing unspoken words, or offering silent blessings.

·What to do: Light the item in a safe, fireproof container. Focus on the flame. Use this time to “speak” to your loved one in your heart or simply sit in mindful silence.

Stage 4: Quietly Moving Forward

·Traditional aspect: Letting the fire burn out completely and handling the ashes respectfully.

·Modern meaning: The quiet time after the flame goes out is for letting emotions settle. It symbolizes completion—your message has been “sent.” This pause allows you to find a sense of peace and closure before returning to daily life.

·What to do: Sit quietly for a few moments. Take a deep breath. Notice how you feel. Then, respectfully dispose of the cooled ashes.

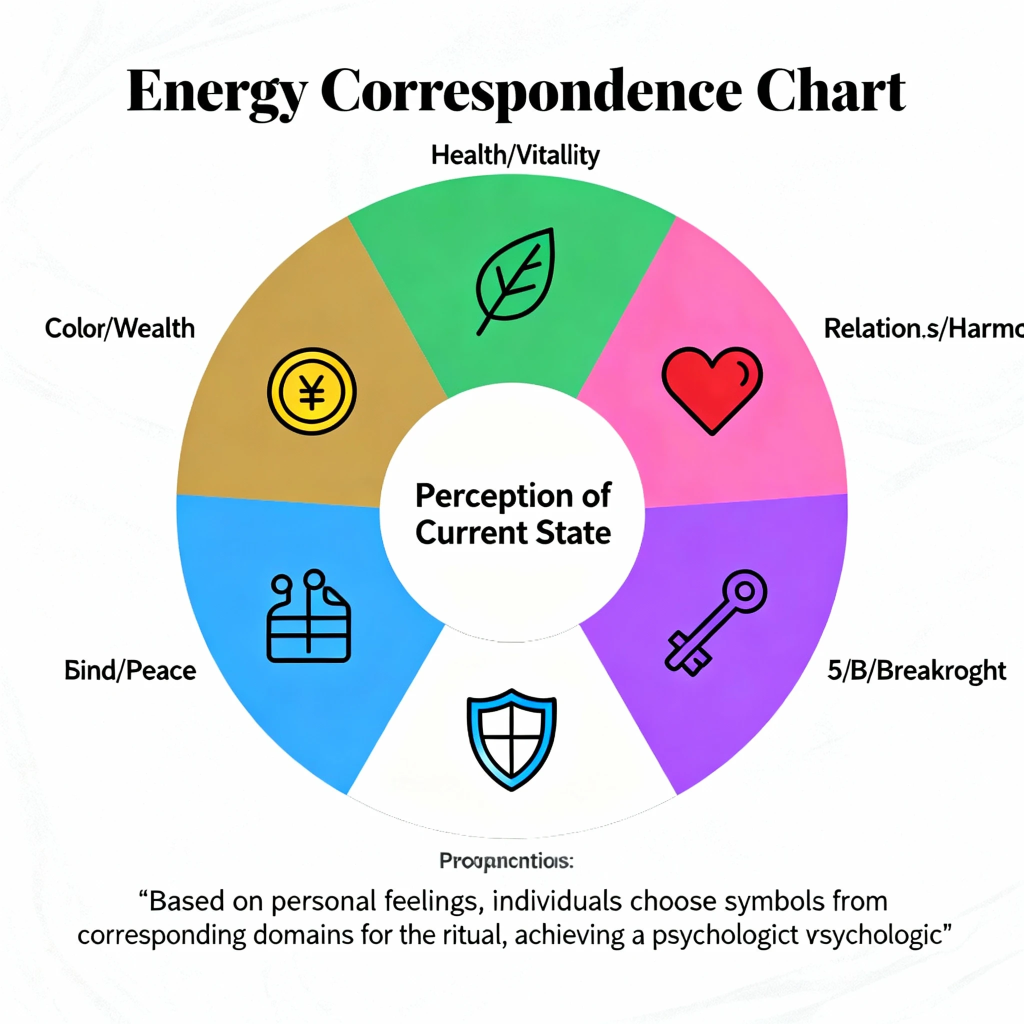

Part 3: Addressing Needs Through Symbolism – The Ritual’s Adaptive Wisdom

A particularly meaningful aspect of this tradition is its ability to adapt to different life situations. At its core is the idea of symbolic connection: using items that visually or meaningfully represent a specific need or wish, as a way to focus intention and seek balance.

Modern psychology sees this as a way of using external symbols to influence our internal state—a tangible practice for managing thoughts and emotions.

| Life Situation | Traditional Symbolic Items | Symbolic Meaning | Modern Psychological View |

| Feeling stuck, seeking a way forward | Paper bridge; figure of a “path-clearing” deity | Creating a passage; removing obstacles. | Reclaiming a sense of agency. Turning an inner feeling of being “blocked” into a visible symbol that can be “burned away” or “built” helps shift from a passive to a more empowered mindset. |

| Seeking financial stability | Gold paper ingots; replica coins | Direct symbols of material wealth and security. | Focusing intention & easing anxiety. Ritually addressing money worries through a concrete act can provide temporary relief from stress and may help one become more aware of real opportunities. |

| Concern for health | Paper longevity peaches; green paper leaves | Symbols of long life and vitality. | Reinforcing a health commitment. Performing a ritual centered on well-being acts as a form of self-encouragement, often motivating more practical health actions afterward—like better rest or a doctor’s visit. |

| Mending relationships | Red “reconciliation flowers”; a cut black thread | Seeking harmony; cutting ties to conflict. | Finding emotional closure. Symbolically “burning” discord or “tying” a bond helps release lingering resentment and can prepare the heart either to repair a relationship or to let go and move on. |

| Mental restlessness, seeking clarity | White paper lantern; writing down worries to burn | Bringing light to confusion; clearing the mind. | Mental decluttering through ritual. The act of “writing it down and burning it” is a recognized way to manage worries. It externalizes circling thoughts and, through the ritual, creates a feeling of release and mental clarity. |

Part 4: Cross-Cultural Reflections – A Universal Language of Remembrance

The practice of honoring those who have passed is not unique to any one culture. Around the world, people have developed their own ways to express love, memory, and connection—each using a different “language” to convey similar human feelings.

• Western Cemetery Visits

This tradition centers on a fixed, physical place—the gravesite. Bringing flowers, cleaning the headstone, or speaking quietly at the site creates a sense of ongoing connection and private reflection in a dedicated space.

• Mexico’s Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos)

Here, remembrance is vibrant and communal. Families build colorful altars, share favorite foods, and decorate with marigolds to welcome back the spirits of loved ones. It’s less about mourning and more about celebrating life together, blurring the line between the living and the departed.

• Online Digital Memorials

In the digital age, remembrance has entered virtual space. Through memorial websites or social media pages, people can leave messages, light virtual candles, and share photos—creating a lasting, accessible archive of memory that transcends time and location.

What ties these practices together—and links them to traditions like “proxy burning”—is a shared pattern:

1.Recognizing a need—to remember, to honor, to feel close.

2.Choosing a medium—whether fire, flowers, food, or words.

3.Performing a ritual—burning, placing, arranging, writing.

4.Finding comfort—completing an act of love, and in doing so, bringing peace to the heart.

Across cultures, these rituals help us process loss, express love, and stay connected to something—or someone—beyond our everyday reach.

Closing Thoughts: A Broader Understanding – and an Open Invitation

Understanding traditions like joss paper burning is not about endorsing or dismissing them outright. It’s about expanding our view of how humans everywhere find ways to cope with life’s deepest questions—death, memory, uncertainty, and love.

This perspective invites us to:

1.Honor the role of ritual in emotional life

Recognize that structured acts of remembrance—whatever form they take—can provide real comfort and help process feelings that are hard to express in words alone.

2.Appreciate the creativity of cultural symbols

See how people across time and place have turned deep needs into meaningful practices using objects, actions, and shared traditions.

3.Find your own way to meaning

You don’t have to follow a specific tradition to benefit from its core idea: that intentional, symbolic actions can help clarify your thoughts, focus your intentions, and bring inner calm.

A Simple Personal Practice to Try

Next time you’re holding onto something—a regret, a strong wish, or the memory of someone important—you might try this gentle, symbolic process:

·Clarify

Put your core feeling or wish into one clear sentence.

·Symbolize

Choose or make a simple object to represent it—a leaf for letting go, a stone for stability, a written note.

·Ritualize

In a quiet moment, treat this object with care. You might safely burn it, bury it, set it in flowing water, or place it somewhere meaningful.

·Integrate

Sit quietly afterward. Notice what you feel. Then carry that clarified intention into your day.

At its heart, rituals like these are about transforming what weighs on us inside—not to change the outer world through magic, but to regain the clarity, peace, and strength we need to move forward. They remind us that even in loss or uncertainty, we can create moments of meaning, connection, and renewal.